Generations of marketers have encouraged parents to raise the seated height of their child in the family car: for industry it’s an article of faith, it gives the high-back booster seat its primal appeal.

But by elevating and advancing the child, a high-back booster seat makes it far more likely she will impact the interior of the vehicle in a collision and suffer a head injury.

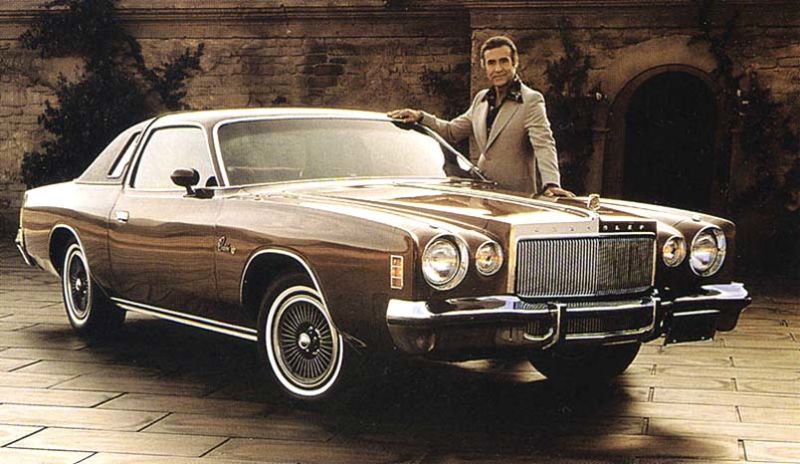

Especially in today’s smaller cars. The booster seat we know today was invented at a time when our concept of a small car looked like this:

The cars of the seventies were not particularly crashworthy but their vast interior space could keep a child seated in the middle of the back seat far enough away from impact surfaces. Regulators of the day were nonethless preoccupied primarily with risk of head injury and the DoT (U.S.) child car seat specification MVSS 213 reflected their preoccupation; it also reflected the generous interior dimensions of the cars of the period.

The principle criterion of MVSS 213 was a limit on head excursion of 32 inches (813 mm). As it was in 1976, so it is today. The specification has not been adapted to the reality of today’s smaller cars.

The reason? High-back booster seats wouldn’t pass.

A child is safest and at lowest risk of head injury sitting with her back against the seat of the car on a booster cushion just tall enough to allow her to bend her legs at the knees. A high-back booster seat moves her a diagonal distance of 8 to 12 inches away from the seat bight (the intersection of the back of the seat and the sitting surface) and that much closer to either the back of the front seat or either side of the interior of the vehicle in a collision.

The risk to the child increases when she slouches. Bad posture is antithetical to effective lap belt restraint but many high-back booster seats encourage the child to slump forward, as shown by this top-rated model, resulting in:

- a further extension of the lap belt and a corresponding increase in the displacement of the child towards an impact surface in a collision ;

- the counter-clockwise rotation of the child’s pelvis, increasing the likelihood of the lap belt riding over the pelvic spines to penetrate the abdomen;

- a reduction in the angle of the lap belt, increasing the risk of the child ‘submarining’ under the belt in a collision.

There is a tragic irony to this because the original purpose of the booster seat was to position the lap belt so as to reduce the risk of ‘seat belt syndrome’.

A high-back booster can retail for as much as twenty times the the price of a backless booster, and booster seat advocates have switched their emphasis from avoidance of seat belt syndrome through use of a booster cushion to improving shoulder belt fit to reduce neck injuries with a high-back booster.

But serious neck injuries among children are practically nonexistent and static shoulder belt fit with a high-back booster is meaningless in a collision when it is dependent upon a plastic feature of the seat, or when a child rolls out of her shoulder belt due to lateral collision forces.

The shoulder belt can play an important role in limiting head excursion and sharing collision loads otherwise concentrated on the child by the lap belt in a frontal collision but only a minority of real-life collisions are cases of pure frontal impact.

Meanwhile, high-back booster seats extend lap seat belts to move the child closer to forward and lateral impact surfaces, more than doubling her chances of suffering the most devastating collision injury.