Go to any Walmart or ToysRus and the aisle where you find the high-back booster seats is the loneliest section of the store. The atmosphere is funereal, it’s a wake for a product at the end of its life cycle, one that nobody is going to celebrate after it’s gone.

Authorities advise the use of booster seats but our horse sense makes us ask, why? Parents find themselves in a state of conflict, their reasoning arrested somewhere between conventional wisdom (good parents use booster seats) and common sense (I don’t see how they make my child any safer).

Not surprisingly, booster seat use plateaued at 43 per cent a decade ago.

Booster seat advocates tell us that even though a booster seat is not a child restraint their products nonetheless reduce injuries among children 4 to 8 years of age by 45 per cent compared to use of seat belts alone. Really?

They don’t. And it’s time to lift the veil.

Because the opposite is true. Recent analysis of data from the 1998 through 2009 National Automotive Sampling System (NASS) Crashworthiness Data System (CDS) at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) School of Public Health found :

- children in booster seats are at 52 per cent higher overall risk of serious (AIS 2+) non-fatal injury than children restrained by seat belts alone;

- the risk of serious (AIS 2+) head injury is 157 per cent higher for children in booster seats.

It’s hard to accept that parents have been misled and their children put at risk.

It’s harder still to accept this is the result of a campaign of misinformation.

The thin edge of the wedge of this campaign – the widely circulated ’45 per cent’ statistic – comes from a 2009 study sponsored by State Farm Insurance at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) which analyzed crash data supplied by State Farm.

Authors of the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) School of Public Health study point out that the findings of the State Farm study ‘do not appear to be consistent across different databases’.

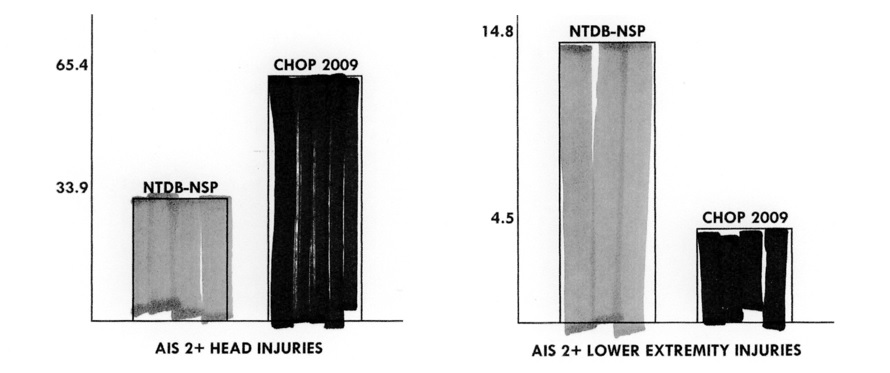

There are striking differences between the State Farm data and that of the U.S. National Trauma Data Bank (NTDB) for the same interval : for example, the rate of head injury among children in the State Farm database (65.4 per cent) is roughly double the rate of head injury of children in the national database (33.9 per cent).

Although the 2009 CHOP study claimed to compare children in booster seats with children in seat belts, comparison of the State Farm data with the national database leads to the inevitable conclusion that in the State Farm study the children in booster seats were compared, not to children all wearing seat belts as stated, but with children who in the majority were altogether unrestrained.

State Farm chose to analyse internal data describing only a subset of the entire population of booster-age children in collisions.

A legitimate database for such a comparative study would contain only collision data collected by third-party observation on the basis of objective criteria and would include all of the occupants of the vehicle(s) involved in each of the collisions.

In contrast, the State Farm database was based on claims by policy holders ; researchers who processed the data sought corroboration from the parents and guardians of the children either killed or injured.

The most fundamental flaw in the database was its composition of only the children injured in automobile accidents, not all children involved in those accidents, injured or not. As such, the database had an inherent bias against use of seat belts alone : children who were not injured because they were wearing seat belts were not included in the data; children who were unrestrained, and more likely to be injured were included in disproportionately large numbers, and were misclassified by researchers as wearing seat belts.

A comparison such as the above of the injury profiles of the State Farm database with those of the U.S. National Trauma Data Bank (NTDB) for the same interval would have indicated there was something very wrong with the study; a relatively simple arithmetic extrapolation based on that comparison would have indicated a probability that booster seats more than doubled head injuries, consistent with the recent studies at the UAB School of Public Health.

This comparison, if ever made, never received public attention. The CHOP study received the imprimatur of The American Academy of Pediatrics and ’45 per cent injury reduction’ became the headline of a campaign to insinuate the booster seat into our daily lives and diffuse concern over the safety of young backseat passengers.

The booster seat has managed to lurk under the regulatory radar over the years because it is not really a restraint.

And that is its genius : as a child seat which doesn’t actually restrain the child, the belt-positioning booster seat is the perfect product for litigious times.

Perfect for booster seat manufacturers and their insurers, that is, because it limits their liability when it is the vehicle seat belt and not the booster seat which restrains and thus injures a child.